November 2, 2023 • JASE

COVID-19 Statement Update

ASE COVID-19 Statement Update: Lessons Learned and Preparation for Future Pandemics

January 27, 2021 • JASE

Adapting Pediatric, Fetal and CHD Services COVID-19

ASE Statement on Adapting Pediatric, Fetal, and Congenital Heart Disease Echocardiographic Services to the Evolving COVID-19 Pandemic

May 19, 2020 • JASE

Reintroduction of Echo During COVID-19

ASE Statement on the Reintroduction of Echocardiography Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic

April 7, 2020 • JASE

ASE Statement on COVID-19

ASE Statement on Protection of Patients and Echocardiography Service Providers During the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak: Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology

November 1, 2005 • JASE

Minimum Standards for the Cardiac Sonographer

American Society of Echocardiography Minimum Standards for the Cardiac Sonographer: A Position Paper

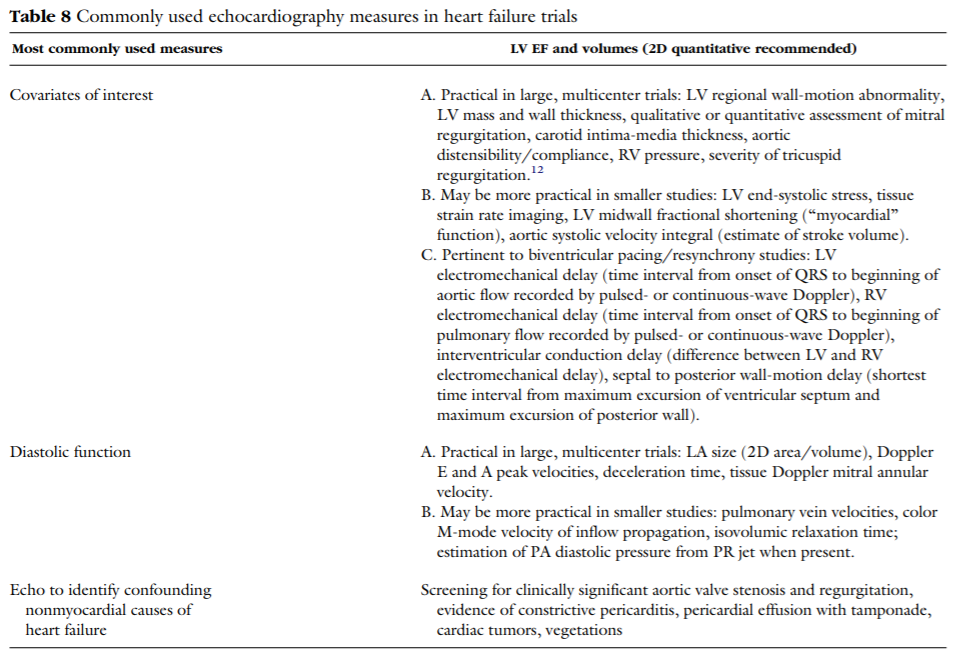

October 1, 2004 • JASE

Echo in Clinical Trials

American Society of Echocardiography Recommendations for Use of Echocardiography in Clinical Trials